Understanding the Compliance and Voluntary Carbon Trading Markets

27/06/2024

As the drive to curb global climate change gathers momentum, carbon markets have become increasingly fundamental to achieving the Net-Zero greenhouse-gas emissions target. Net Zero refers to achieving an overall balance between emissions produced and emissions taken out of the atmosphere. Information from the UN shows over 130 countries have now set or are considering a target of reducing emissions to Net Zero by 20501.

Reducing the level of greenhouse gasses (GHG) in the atmosphere is vital for limiting the damaging impacts of climate change. This can be tackled through both the compliance market (mandatory market) and the voluntary market. Compliance markets are regulated by mandatory national, regional, or international carbon reduction regime and is usually aimed at energy intensive emitters such as iron and steel producers, oil refineries, power generators, airlines, and processing companies. Whereas, voluntary markets function outside of compliance markets, therefore they do not currently involve any direct government or regulatory oversight.

Demand for voluntary carbon credits (VCC’s) is set to rise by a factor of 15 by 2030 and with the need of more than a 100-fold increase for us to achieve Net Zero by 2050, says the Taskforce on Scaling Voluntary Carbon Markets2. VCC’s usually serve businesses, government departments and individuals wanting to be accountable for their carbon footprint.

Carbon markets are an essential driving force in helping us stay within the bounds of our global carbon budget, by effectively putting a price on pollution. Here we highlight key aspects of both carbon markets, key challenges and outline how your business can build climate action strategies to enforce a robust end-to-end trade lifecycle.

What is the compliance carbon market?

The compliance market aims to establish a carbon price by laws or regulations which control the supply of allowances that are then distributed by national, regional, and global regimes. This can be accomplished through either a carbon tax or a cap-and-trade scheme, shifting economic incentives by making it more expensive to pollute. Over 60 countries have to date implemented such mechanisms to meet their emissions reduction targets, known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC)3., set out in the Paris Agreement.

The European carbon compliance market and how it operates

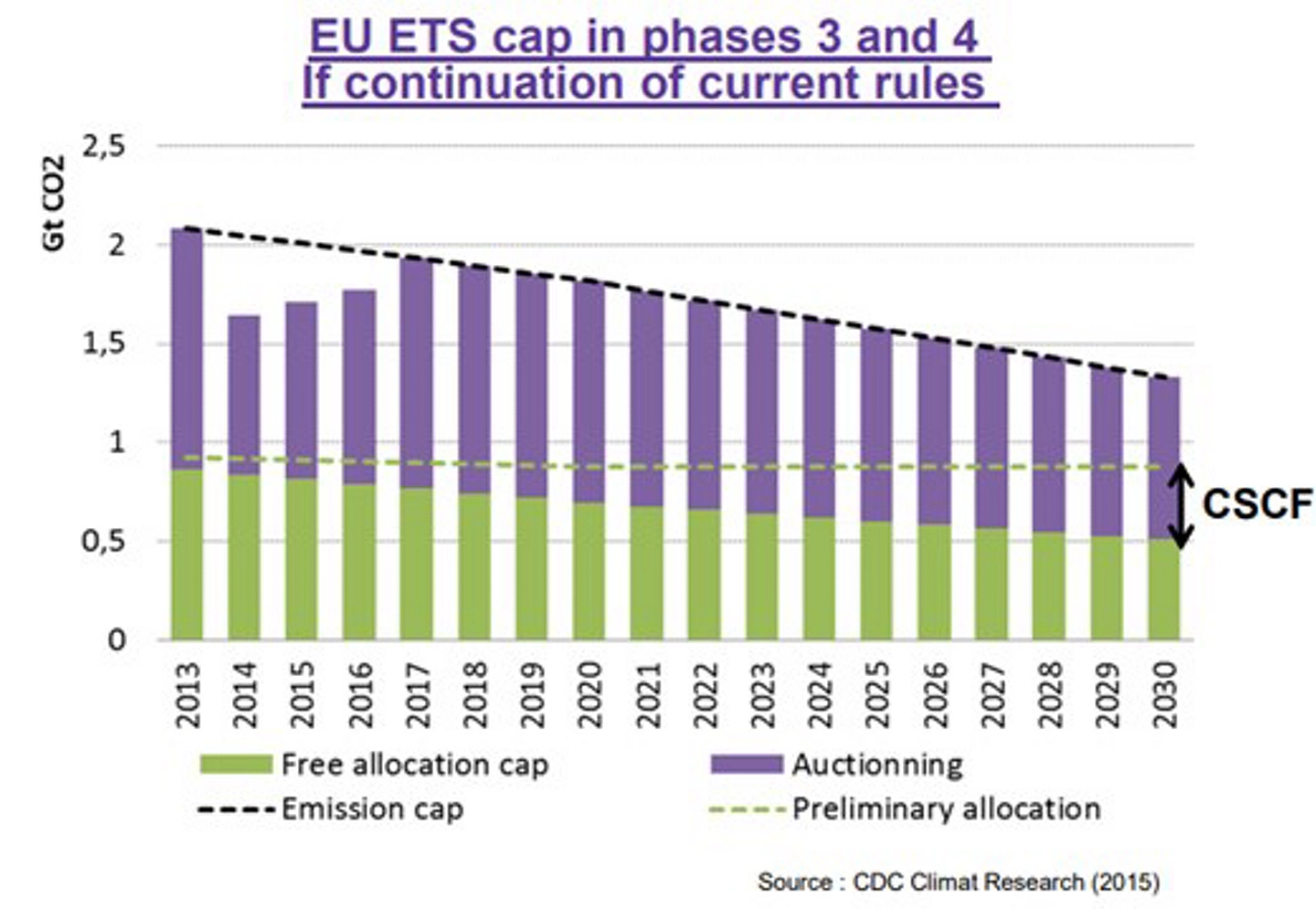

The European Union Emissions Trading System (EU ETS), established in 2005, is the world’s first major carbon market. The EU ETS regulates around 11 thousand installations across different sectors from heat and power generation to energy intensive industry sectors. The EU ETS works on the cap-and-trade principle. A cap or limit is set on the total amount of specific greenhouse gases that can be emitted by the installations covered by the system. The cap is reduced over time so that total emissions fall. This is highlighted in the diagram below.

An entity must surrender enough allowances to cover its emissions production on a yearly basis, otherwise fines are imposed. If an entity reduces its emissions, it can keep the spare allowances to cover its future needs or sell them to another party that is short of allowances. Entities can therefore trade emission allowances with one another as required.

How carbon credits are traded and distributed in the compliance market

Carbon credits such as EUAs (EU Allowances) are classed as derivatives, these can be traded in spot, forward and future markets which are subject to MiFID II regulations. The EUA market has developed both a liquid primary and secondary market. In the primary market, a certain share of the total allowances is allocated free of charge to operators, other EUAs are reserved for supporting specific funds such as innovation and transformation projects. The remainder is sold through auctions4.

Auctions are run by appointed auction platforms, which are predominantly on ICE and EEX. There are daily and monthly auctions which vary in volume. To partake in the auctions of buying and selling future contracts on EUAs, you must either be a direct market participant with a registry account or use a broker / bank to facilitate this on your behalf. Once the emission allowances have been put into circulation by EU companies, they can be traded by any party that has an EU registry account in the secondary market. Within the registry account, parties can buy and sell EUAs over the counter (OTC).

As a result of Brexit, the UK now manages and runs its own carbon emissions programme called the United Kingdom Emissions Trading System (UK ETS), where UKAs (UK Allowances) are traded on the UK registry. The US doesn’t have a carbon tax at a national level but has several at State level including California, Oregon, Washington, Hawaii, Pennsylvania and Massachusetts5. China has also recently launched an Emissions Trading scheme (ETS) in July 2021, covering approximately 4.5 billion tonnes of CO2 per year, or around 40% of China’s total.6

The challenges faced by the compliance market

- It is not easy to determine the appropriate level at which to set the cap, an over allocation could prove to be ineffective in reducing GHG, whilst a stringent allocation could have severe economic costs.

- Some argue that the cost of failing to comply with the CAP limit is relatively inexpensive, the current penalty is as low as 100 Euros per excess ton of C02 produced over the Cap. Whereas the cost to purchase an EUA is currently just above 807 Euros8.

What is the voluntary carbon market?

Voluntary markets are incentive-based markets that allow individuals and entities to purchase VCC’S to compensate for any residual or unavoidable carbon emissions on a voluntary basis. Strategies to avoid, reduce and substitute harmful greenhouse gases must come before offsetting, but there are emissions being produced that are unavoidable due to a lack of current technology and cost. Each credit represents one tonne of CO2 (or equivalent GHG) reduced or removed that has been independently verified.

There are two schemes available to offset carbon emissions. The first being a reduction scheme, which aims to cut emissions by improving existing processes. The second being removal projects that aim to absorb greenhouse gases from the atmosphere, either through nature-based solutions like re-forestation, or through technology-based projects such as carbon capture and carbon storage. Businesses that are striving towards Net Zero will usually consider removal projects, given the focus is on removing GHG out of the atmosphere, whilst businesses whose goals are to achieve carbon-neutrality will typically consider reduction projects for delivering CO2 offsetting.

Where are carbon offset credits acquired and retired?

VCC’s can be purchased directly from suppliers in registries, such as Verra, American Carbon Registry, Gold Standard, Climate Action Reserve. Alternatively, VCC’s can be purchased through brokers or exchanges such as CBL and ACX. Some examples of buyers include corporations, airlines, and governments with emissions-reduction goals.

The holder of a VCC must “retire” the credits in order to claim their associated GHG reductions towards a GHG reduction goal. VCC’s can also be retired on behalf of third parties. Retirement occurs according to a process specified by each carbon offset program’s registry. Once an VCC is retired, it cannot be transferred or used (meaning it is effectively taken out of circulation). Retirements can be made public at the time of processing.

The challenges faced by the voluntary carbon market

- There’s scepticism around the quality of VCC’s. Carbon offsets offered by world leading carbon standard providers, have been widely criticised for overrepresenting the amount of carbon reduction they are causing. This impacts consumer confidence and makes it increasingly difficult to distinguish between high and low quality VCC’s.

- Price transparency, each project is unique from the vintage to the offset project type. Both buyers and sellers alike are facing the problem of price discovery, particularly with the more obscure projects. This provides a challenge for traders who need an accurate live and end of day price to create and mark their PnL (Profit and Loss) and M2M (Mark to Market).

- There are varying rules, criteria, and methodology dependent on the standard provider. This in addition to the numerous registries and exchanges can make it difficult to navigate around these platforms to transfer and retire credits, as well as producing the required certificates within the registries themselves.

References:

1 Global net zero commitments (parliament.uk)

2 The mission to mend the voluntary carbon offset market – Energy Monitor

3 All About the NDCs | United Nations

4 Primary and secondary market – Emissionshaendler.com

5 Explainer: Which countries have introduced a carbon tax? | World Economic Forum (weforum.org)

6 The first year of China’s national carbon market, reviewed (chinadialogue.net)

7 EU Carbon Price Tracker | Ember (ember-climate.org)

8 15-06-29 CEPS meeting_CDC Climat Research_EU ETS Free allocation

Hemal Pandya | Tim Archer – Deloitte